No sooner had I figured out that math behind 4d6, drop the lowest, then it seems I was confronted with the gamer practice of rolling 4 six sided dice, re-rolling any 1s, and then dropping the lowest score. One gamer decided just to take my 4d6 math and convert it to 4d5 math figuring that re-rolling 1s meant perpetually re-rolling 1s. Of course, as I asked in the thread, if you’re going to re-roll a 1 every time you get it, why on Earth are you rolling a six sided die to begin with. The dice bag of most D&D/Pathfinder players tends to have more dice than they know what to do with. Wouldn’t it make more sense to just roll four 5 sided dice (which really means you roll a 10 sided die and divide it by two, rounding up) and then add 1 to each die’s result. Doing so would give the same results as 4d6 with a perpetual re-roll and would not involve the seemingly tedious step of re-rolling anything.

Of course most people aren’t as elegance minded as I am, but I also suspect that most people have the habit of re-rolling 1s once and then taking the result whatever it is. My friend Taylor had just asked me a couple of weeks ago how to figure the math on a six sided die with a single re-roll of 1s. That math is actually quite simple. When you roll a six sided die, the chance of getting any particular result is 1 out of six, or .1666 repeating. Now when you roll a one, it creates a new probability event and you re-roll. So for the die to end up on a one would require you to roll a 1 twice in a row. So the odds are 1/6 times 1/6 or 1 in 36, .02777 repeating. Of course, the chances of you rolling a 1 and then rolling any number are the same .02777, so all you need to do is add that amount to the other scores. Thusly, the probability of getting any particular result on a single six sided die with a single re-roll of 1s is:

Result Probability

1 1/36 or .02777

2 7/36 or .19444

3 7/36 or .19444

4 7/36 or .19444

5 7/36 or .19444

6 7/36 or .19444

Simple enough. But what about the problem of 4d6, single re-roll 1s, and drop the low result? We know for last time that there are 1296 possible combinations of four six sided dice. When we single reroll a 1 result, we still end up with 1296 possible combinations, we’ve simply weighted some more heavily than others. In the problem with a single re-roll of a six sided die, a 1 is still a possible result, it’s just much less likely than any other possible result. Similarly, I figure in the 4d6 problem that there are still 1296 possible results, but we just need to weight them differently. It’s still possible to get a result of (1,1,1,1) on four six sided dice, it’s just much less likely than (6,6,6,6), but how much less likely?

Well, we can see from the six sided die result that getting a result of a six is 7 out of 36, whereas a 1 is only 1 out of 36. If we compare the two probabilities by dividing the chances of the 1 result by the chances of the 6 result, we get 1/36 divided by 7/36, which simplifies to 1 in 7, or .14286. That is, you are the comparative probability of getting a 1, rather than a six (or any other score) is .14286. So if we take an array or results and we weight all the results with 1s by .14286, we should get the results of the array weighted so that 1s are far less likely.

Let’s take a look at a single six sided die’s results to check our work. A six sided die has an equal probability of generating a 1,2,3,4,5, or 6. Each has a probability of 1 in 6. If we multiply the 1 result by 1 in 7 (or .14296) then, we get the following table.

Result Weighted ProbabilityRe-Weighted Probability

| 1 | 1/42 | 1/36 | 2 | 1/6 | 7/36 | 3 | 1/6 | 7/36 | 4 | 1/6 | 7/36 | 5 | 1/6 | 7/36 | 6 | 1/6 | 7/36 |

The problem here is that the probabilities do not add up to 1 anymore like they are supposed to, but we can re weight them by adding up everything and dividing each probability by the sum. If we add up all the probabilities above, we get 5/6 + 1/42, or 35/42 + 1/42 = 36/42 or .857. If we now divide each probability by the sum of 36/42, we get the re-weighted probability in the column in the table above. Voila! The re-weighted probability is exactly equal to the original probability we calculated in the first table.

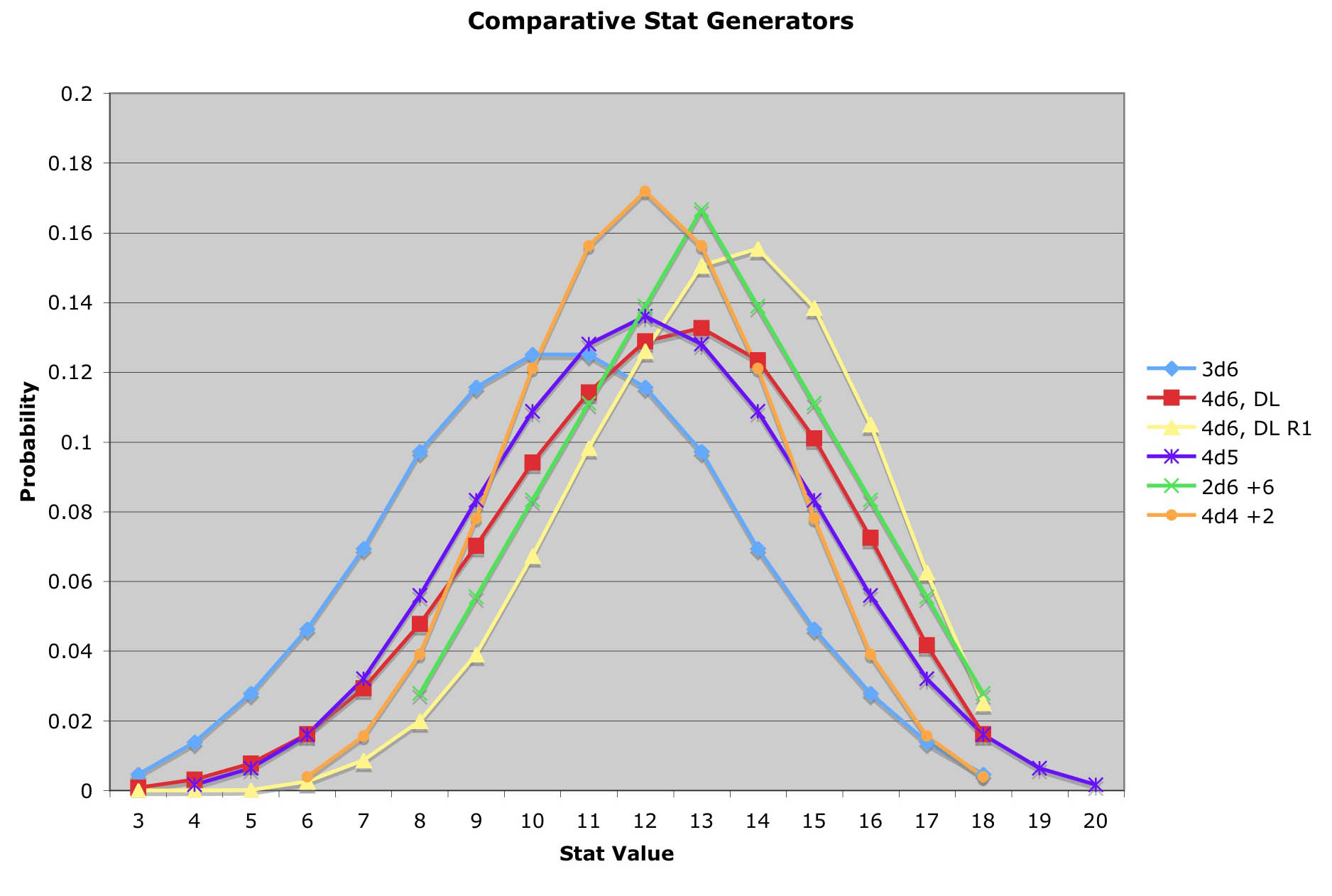

What this means is that we can take any array of six sided die results, multiply each result that has a 1 by 1/7 for each 1 it has, re weight the results, and we will get the precise probability of getting each result with a single re roll of ones. If you’re curious, I can show how any exact probability was calculated. Most people don’t care, so I’m leaving that off. Here are each of the following commonly used stat generation methods in D&D/Pathfinder: 2d6+6, 4d6 drop the low, 4d6 with a single re-roll of 1s and drop the low, 3d6+2, and new method I’m proposing which is just 4d5 keep all. I graphed the probabilities of each against their respective scores and got the following graph:

Here’s the data that went into generating this graph.

Number2d6+63d64d6, DL4d6, DL, R14d54d4+2

| 3 | .00463 | .0007716 | 5.96eE-07 | ||||

| 4 | .0139 | .003086 | 1.67eE-05 | .0016 | |||

| 5 | .0278 | .007716 | .000192 | .0064 | |||

| 6 | .0463 | .0162 | .00262 | .016 | .003906 | ||

| 7 | .0694 | .0293 | .00873 | .032 | .01563 | ||

| 8 | .0278 | .0972 | .0478 | .0199 | .056 | .03906 | |

| 9 | .0556 | .115 | .0702 | .0391 | .0832 | .07813 | |

| 10 | .0833 | .125 | .0941 | .0674 | .1088 | .1211 | |

| 11 | .111 | .125 | .114 | .0983 | .128 | .1563 | |

| 12 | .139 | .116 | .129 | .126 | .136 | .1719 | |

| 13 | .167 | .0972 | .133 | .150 | .128 | .1563 | |

| 14 | .139 | .0694 | .123 | .155 | .1088 | .1211 | |

| 15 | .111 | .0463 | .101 | .138 | .0832 | .07813 | |

| 16 | .083 | .0278 | .073 | .105 | .056 | .03906 | |

| 17 | .0556 | .0139 | .0417 | .0626 | .032 | .1563 | |

| 18 | .028 | .00463 | .0162 | .0252.016.003906 | |||

| 19 | .0064 | ||||||

| 20 | .0016 |